If you’ve been around the international development business long enough, you’ve probably heard someone ask, “So, what do we know about what works?” Maybe it’s a parliamentarian, a minister, or the Administrator of USAID. Maybe it’s a reporter. Or maybe it’s a newly arrived junior member of a project team, hoping her middle-aged colleagues—who clearly have all the answers—will rattle off a list of evidence-based interventions to improve health, teach kids, empower women, or reform the civil service.

The response depends on who’s doing the answering. “Old development hands,” the folks who have worked in dozens of countries on project after project, are likely to say we know a lot about what works, and success depends on community engagement (or gender-sensitive project design, or careful monitoring, or something else hard-won experience has convinced them is critical but too-often overlooked). Members of the research community will often say we know very little—maybe even nothing—because few interventions have been subject to rigorous evaluation, or the respondents haven’t had time to keep up on the literature. If the person answering happens to have done a systematic review of all the research on a particular topic, the response will be an exhaustive (and thoroughly exhausting) review of what works and what doesn’t. And the rest of us? Well, we’ll just shrug—or bluff.

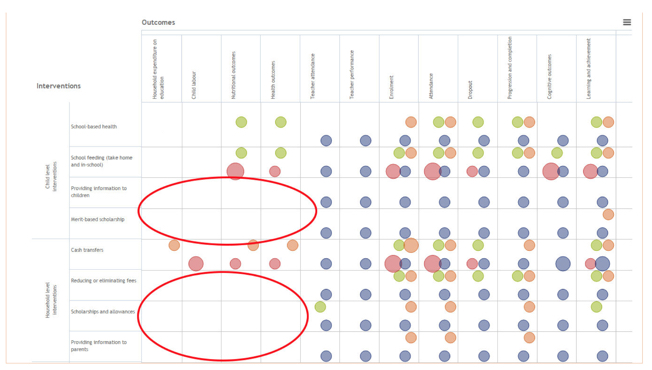

That’s why I love the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation’s Evidence Gap Maps, elegant, colorful visualizations of what we know and what we have yet to discover. Based on searches for all relevant impact evaluations and systematic reviews on a given topic, the maps are a one-stop-evidence-shop for expert and curious non-expert alike. They make us smarter.

Take, for example, the question of what we know about how to improve teaching, pupil attendance, and learning outcomes in primary and secondary school. A pretty important question. The 3ie Evidence Gap Map displays on a single page how interventions like school meals, scholarships, cash transfers, teacher incentives and community monitoring affect each of these outcomes. For well-studied interventions, you can click through to curated impact evaluations and systematic reviews. For interventions that have rarely or never been evaluated, the white space tells the tale of a major evidence gap. Like all the Gap Maps, the one on education captures far more research than most people have time or energy to sift through.

Just as geographic maps chart territory without telling you precisely where to go, the Evidence Gap Maps themselves don’t offer recommendations for policy or practice. But they tell us what studies are most relevant to our specific question and context, and are an invaluable tool to help those in the research community (and their funders) set priorities.

It is precisely to help set research priorities that we’ve started working with 3ie on an Evidence Gap Map on adolescent reproductive health programs and outcomes. We’re at the start of the process, which entails precisely defining what we mean by “adolescent” and “reproductive health programs,” and what outcomes—from youth empowerment to pregnancy prevention—we and other funders might want to learn most about. The next few months will be filled with extensive literature searches, and then sorting, synthesizing, and summarizing.

My colleagues and I are eager to see the result, because we’ll be able to hone in on the questions that have been investigated the least, which in turn will help us focus our (always limited) research dollars. Best of all, we won’t have to resort to outdated experience or whatever research findings we happen to remember when someone asks, “So, what do we know about what works?”