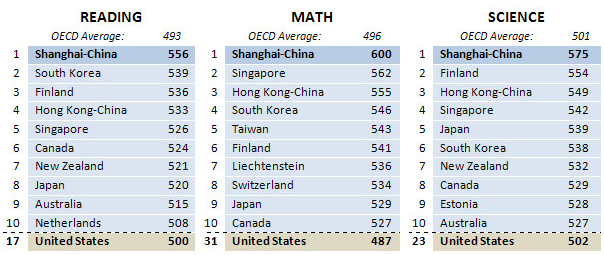

Americans were stunned when fifteen-year-olds from Shanghai, China, led the world while U.S. students lagged far behind in the results of a respected international exam released in December. How did American students do? They trailed Poland in math and science.

It was the first time mainland Chinese students had taken the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and their commanding lead among sixty-five countries and school systems underscored the urgency of the Hewlett Foundation’s updated Education Program strategy focused on “deeper learning.” Here was impressive new proof that the nation’s schools must make drastic changes in what and how they teach if the United States is to keep pace with the most powerful international players in the digital age.

“We can quibble, or we can face the brutal truth that we’re being out-educated,” Secretary of Education Arne Duncan told the New York Times when the 2009 PISA scores in reading, math, and science were released. He noted that U.S. students ranked “23rd or 24th in most subjects.”

Deeper Learning, Greater Advantage

PISA is designed to measure not just whether students know basic facts but whether they can use them in practical situations. Researchers consider the exam an excellent measure of the analytical and academic skills the Foundation’s Education Program has identified as critical elements of deeper learning.

The goal of deeper learning is to prepare students to graduate from high school and college with the capacity to know and understand core academic content, think critically and solve problems, communicate effectively, work collaboratively, and continue learning throughout their lives. Education and business experts consulted during development of the Program’s revised strategy argued that students need this combination of knowledge and skills to succeed in a global economy.

The stakes are high. Eric Hanushek, a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution who co-authored a paper last year on the fiscal impact of educational performance, found a strong correlation between a nation’s PISA scores and its economic growth. He calculated that raising average scores on PISA by just twenty-five points—on a scale where 500 is always the international average—could increase the gross domestic product of the United States by $45 trillion over the lifespan of children born in 2010.

PISA goes beyond measuring rote knowledge to examine how well students reason and communicate as they interpret information and solve problems. As an example, the reading section of the test requires students to consider a text and then analyze and reflect upon it in a combination of multiple-choice and written responses. Tasks are designed to mimic the experiences students might encounter in the real world, such as deciphering the warranty for a newly purchased camera.

“PISA focuses on reading to learn rather than learning to read,” says Andreas Schleicher, who heads the testing program for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, headquartered in Paris. The same emphasis on applying knowledge holds true for math and science questions as well.

Helping U.S. Schools Measure Up

The Foundation was so impressed by the exam’s emphasis on analytical and communication skills, one of the first grants in its new Deeper Learning portfolio went to develop a school-based version, called “PISA for Schools.” Although the original PISA measures average achievement at the national level, the new assessment will provide scores for individual schools and districts that voluntarily administer the test to their students.

“Schools will be able to see not just how they compare against the best-performing schools in their own country, but also how they compare against schools in the best-performing nations around the world,” says Schleicher, who is supervising development of “PISA for Schools.” “Equally important, because PISA positions each school in its demographic and social context, schools will be able to see how they compare against schools operating in similar social conditions.”

The Education Program’s initial work in deeper learning will focus on assessments at all levels. In addition to investing in “PISA for Schools,” the Foundation will support two groups of states that won federal Race to the Top funding to develop innovative annual tests for third- through eleventh-grade students.

The state testing groups are designing assessments to measure the knowledge and skills outlined in the Common Core standards, which are the first widely adopted national guidelines for what students should know and be able to do in math and English/language arts, and which the Foundation views as a proxy for deeper learning. Since their introduction last spring, these standards have been adopted by forty-three states.

Testing That Transforms

Chris Domaleski, senior associate at the National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment, sees promise in the movement to redesign tests to emphasize common standards and raise expectations for what all students should learn.

“The old saying, ‘What’s measured is what matters’: there’s something to that,” says Domaleski. He argues that a good test can drive instruction by spelling out what students should learn at each grade level. A test also can serve as an accountability tool, providing a trustworthy evaluation of student achievement. “I think there’s an emerging understanding that we really need assessments to play both roles.”

More complex and challenging tests could advance reforms in the education policies that contribute to U.S. students’ poor performance on international exams such as PISA, says Stanford University Professor Linda Darling-Hammond. She’s senior research advisor to the thirty-one-state SMARTER Balanced Assessment Consortium, a Foundation grantee that won a $160 million grant through the federally funded Race to the Top initiative to develop new online exams tied to the Common Core.

The United States tests its students far more frequently than most other countries, Darling-Hammond points out, but it leans heavily on multiple-choice exams that probe only the most basic knowledge. U.S. students are filling in answer bubbles while “most kids in the world are using their brains to pose and solve problems and explore ideas,” she says.

Most current testing programs “actually undermine the curriculum and the quality of the learning,” Darling-Hammond contends. “The time spent on multiple-choice tests squeezes out the time needed to enable kids to learn more important and more useful skills in many schools.”

In an attempt to turn the tide, the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) is also designing exams. Their assessments will require students to read complicated texts, complete research projects, and work with digital media. PARCC is a coalition of twenty-six states that won a $170 million federal grant to produce new tests. Some of its membership overlaps with the SMARTER coalition.

Ultimately, the objective is to give all students an education that prepares them for college and the careers of tomorrow.