What began three years ago as the crusade of two young Mexican legal activists to exonerate a man wrongly convicted of murder has evolved into an international media phenomena that the two activists hope will spur reforms to the Mexican legal system.

The vehicle for the transformation is the film Presumed Guilty, a ninety-minute documentary funded in part with support from the Hewlett Foundation that legal activists Roberto Hernández and his wife, Ladya Negrete, both Mexican attorneys, created to document the wrongful conviction of Toño Zúñiga, a street vendor in Mexico City.

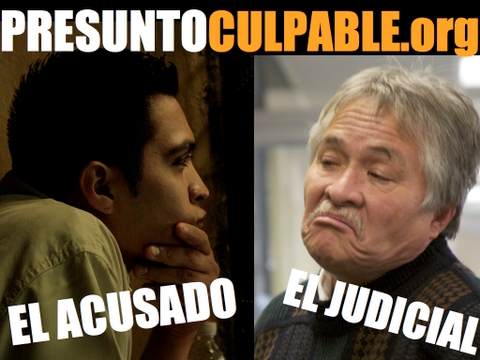

This promotional poster for the documentary Presumed Guilty, a vehicle to tell of the story of the flaws in the Mexican justice system, shows the face-off between the man wrongly accused of murder, Antonio “Toño” Zúñiga, and one of the police officers who arrested him.

To date, Presumed Guilty, has been screened in more than 20 film festivals around the world, winning a dozen awards in the process. Earlier this year it was aired nationally in the United States on the Public Broadcasting Service’s documentary series, Point of View, an honor bestowed on only about two percent of the 1,000 films submitted each year. POV Executive Director Simon Kilmurry estimates the film was seen by more than a million people in the United States when it was broadcast and viewed nearly 10,000 times more online.

But for Hernández and Negrete, all that is merely preamble.

Now, in the wake of the international recognition, they have negotiated an agreement with one of Mexico’s large film exhibitors, and plans are underway for Presumed Guilty to have its theatrical release this fall at movie theatres in Mexico, where they hope it will spur judicial reform.

“If we can show this film widely in Mexico, it will expose common misconceptions in the country,” says Hernández, who with Negrete currently is doing post-graduate work at the University of California at Berkeley.

Negrete adds, “So many Mexicans believe that we have an American [style] courtroom — that we have the prosecutor, the defense, the judge at our trials. They believe that! It is because most have never been in contact with a trial.”

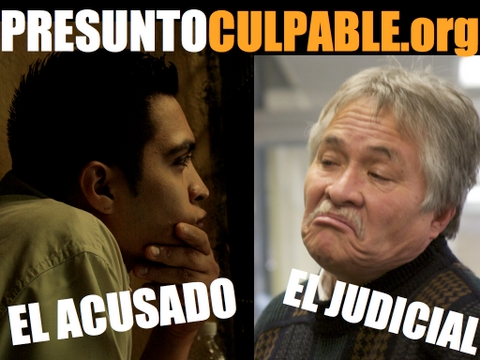

Here the Mexican judge hearing the retrial of Zúñiga’s murder case, gestures to the defendant’s attorney that he rejects a bit of evidence being offered. Zúñiga was re-convicted by this judge and later exonerated on appeal.

Providing funding for the documentary to the nonprofit organizations RENACE ABP in Nuevo Leon and the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of California at Berkeley, where Hernández and Negrete do research, is part of the Hewlett Foundation’s long-term strategy internationally to strengthen local institutions that provide research relevant to government policymakers and the public. Hewlett-supported indigenous think tanks and research centers like the Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (Center for Teaching and Economic Research), the Instituto Mexicano Para la Competitividad (Mexican Institute for Competitiveness), and Centro de Investigación para el Desarrollo (Center of Research for Development) conduct a broad range of social science research that provides objective information to policymakers in Mexico. The goal, in Mexico and elsewhere, is for sound government policy to result in changes that benefit some of the world’s poorest people.

Greater Impact than Research Alone

C.R. Hibbs, program officer and managing director for Mexico for Hewlett’s Global Development Program, says that the film is a powerful way to convey the real world impact of the researchers’ findings about the criminal justice system.

The point seemed to be affirmed in May, when the film was screened for a large group of chiefs of staff for the U.S. Senate and House during a visit to Mexico.

“I’ve worked on human rights in Mexico and worldwide for 20 years and even I have never seen firsthand what happens in a Mexican courtroom,” says Eric Olson, senior associate of the Mexico Institute of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, which helped organize the screening. “It’s a different, visceral way to understand it. It grips people in a way that helps them understand the urgency of making changes.”

Olson, whose Washington, D.C.-based Institute is a part of the Smithsonian Institution, acknowledged that it ultimately is the responsibility of the Mexican people to make these reforms, but added, “Sometimes when attention is brought to these issues abroad the home government tends to take more interest in them. If people in Washington are raising questions, it makes it more important for the Mexican government to do things.”

The story of the film starts in 2007, when friends of the convicted man contacted Hernández and Negrete for help after hearing of research they had done documenting inequities in the Mexican criminal justice system, a system where recent research revealed that 80 to 90 percent of those charged with a crime never even see the judge before being convicted.

For Antonio “Toño” Zúñiga, the nightmare began far earlier, on the morning of December 12, 2005. Walking to the Mexico City plaza where he sold used video games, Zúñiga was arrested by a trio of police detectives and swept into their car. Despite the absence of physical evidence and an airtight alibi, he was charged with and later convicted of murdering a young man a half mile from where he worked and sentenced to twenty years and six months in prison.

The Power of the Camera

From the outset, Hernández and Negrete had decided to attempt to film a retrial of Zúñiga’s case, which he had obtained because the attorney who defended him had falsified his license.

The couple received extraordinary access to the court. The film recounted the workings of a system where there was no presumption of innocence for defendants, no oral trials, and little use of physical evidence. Many, like Zúñiga, were convicted on the word of a single accuser in a written document which, of course, precluded cross-examination. Most never appear before the judge who convicts them. Conviction rates hover around 90 percent.

While the filmmakers had always hoped that the documentary would both help free Zúñiga and serve the cause of reform, they say its success in bringing the problems of the Mexican justice system to a wider audience has succeeded beyond all expectations.

Negrete says that even before the formal release of the film in Mexico, the chief prosecutor of the small Mexican state of Campeche saw the movie and has invited her and Hernández to visit to do research on the justice system there and propose reforms.

Hernández says that recent research by legal scholars in the United States suggests that recording interrogations has the potential to lower the number of false convictions by offering evidence of whether a confession seems credible.

“I think things would change drastically, if they [interrogations] were all videotaped,” he says.

The couple hopes that showing the film in their homeland will encourage Mexican states and the federal government to implement a constitutional amendment that President Felipe Calderón signed in June 2008 to allow fair trials that include the presumption of innocence and the right to oral argument in an open court.

In addition, a judge must be present for all hearings. In the past, a defendant could be convicted and never see or address the judge who convicted him. The reforms also will create a national public security system, with uniform rules for hiring, training, and evaluating the country’s 400,000 police officers. The enacted reforms, which will cost $2 billion to carry out, must be implemented by 2016.

The Slow Road to Reform

Such reforms had been in the works for more than a decade, but two previous presidents were unable to get them through Congress.

“The idea of having fair trials was first mentioned in the Apatzingan Constitution of 1814…and nearly 200 years later, we still have a justice system that presumes guilt,” Hernández says. “As always, the problem is implementation. That’s what we’re after.”

In addition to taping interrogations, he says, reformers would like to see the government adopt recording of police dispatchers’ calls, the use of police lineups, and photo lineups and programs to reduce police corruption, among other changes.

The Mexican attorneys acknowledge that the current drug violence in that country make it a difficult environment in which to seek judicial reforms that support defendants’ rights but remain hopeful that, over time, progress can be made.

Astonishingly, Zúñiga’s retrial, which was before the same judge as the original case, again found him guilty. The transcripts from the retrial simply restated the original trial’s judgment and dismissed any exonerating evidence, including the admission by the sole witness against him that he didn’t see who shot the victim.

Ultimately, it would be Hernández’s and Negrete’s video record of the retrial – the material that would become Presumed Guilty, that would convince an appeals panel to free Zúñiga in April 2008 after 842 days in jail.

From convicted murderer to cause célèbre: Antonio “Toño” Zúñiga, the star of the documentary Presumed Guilty, attended the Mexican opening of the film at the Morelia Film Festival in 2009. Since his exoneration Zúñiga has addressed film-goers about his ordeal. Photo courtesy of Keith Dannemiller.

As for Zúñiga, he has been transformed from victim to reformer. In addition to working as a computer repair technician, he sometimes joins Hernández and Negrete at screenings of the film and stays in touch with others whom he met in prison who also were unjustly convicted.