Q&A with Jonathan Pershing: Can the U.S. still be a climate leader?

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

![Jonathan Pershing [Headshot]](http://www.hewlett.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/HewlettFoundation-0031-JonathanPershing-RT2-300x200.jpg)

Jonathan Pershing, former Special Envoy for Climate Change at the U.S. Department of State and lead U.S. negotiator to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, joined the Hewlett Foundation as environment program director in January. Five months into the job, we sat down with him to discuss the impact of U.S. exit from the Paris climate accord, climate change science, and his early thoughts about environmental philanthropy.

How did you first get involved in global climate diplomacy?

The United States government, working with the American Association to Advance Science (AAAS), supports a remarkable program that puts post-doctoral scientists into government as “fellows.” I was fortunate to be selected for such a fellowship in 1990, and was serving as a science advisor in the State Department when President George H. W. Bush launched the international treaty process to develop what subsequently became the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This agreement had as its objective a goal to stabilize greenhouse gas emissions and avoid human-caused global warming. I participated as a member of the U.S. delegation to these negotiations, and have remained involved (as a diplomat in the State Department, and from outside the government) in support of this agenda ever since.

Over this period, the nature of negotiations changed: the science became clearer, policymakers and global leaders became better informed about climate impact, and the opportunities for change became economically compelling as prices for non-greenhouse gas alternatives turned competitive. For most of the world, these dynamics have led to an increasingly high level of attention to finding and implementing climate solutions. Unfortunately, the U.S. has followed a much more erratic course, with various presidents either actively involved with helping to forge a global consensus on the problem, or repudiating it and withdrawing from the process.

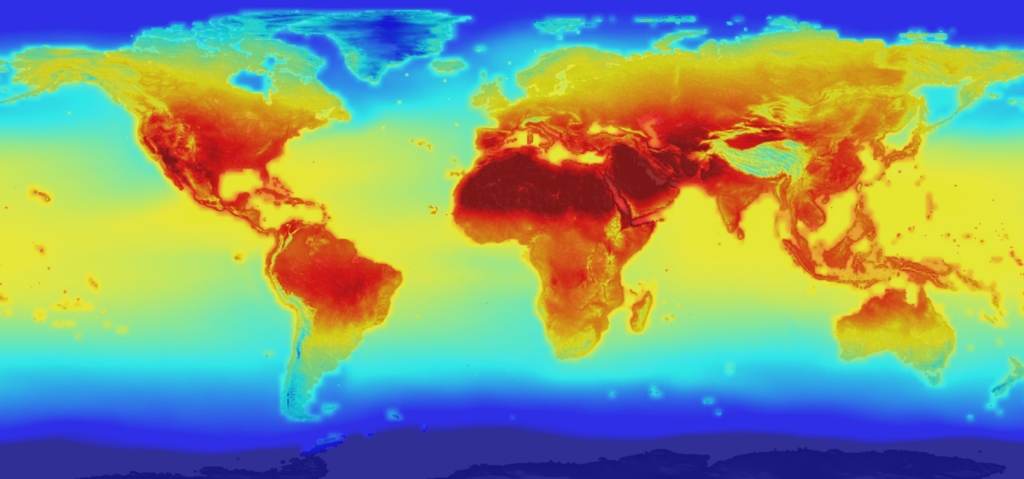

What is climate change doing to our planet now?

We have passed the point at which climate change is only a theoretical problem for future generations; it is increasingly evident around the world. Oceans are warming and Arctic sea ice and glaciers are melting even faster than scientists predicted, causing sea level rise. Stronger storms combined with rising seas are flooding U.S. coastal cities like Virginia Beach, Miami and New Orleans, as well as international cities like Mumbai in India, Guangzhou in China and Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire.

Around New York City, sea level has risen nearly one foot. That made a difference in Superstorm Sandy, when New York City’s South Ferry subway station flooded with 60 feet of water. It took $369 million to repair just that station; the whole system suffered an estimated $5 billion in damages from Sandy. Scientists predict as much as another 4.5 feet of sea level rise there by 2100.

We are seeing ocean acidification, which happens when oceans absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This changes the base of ocean ecosystem and is anticipated to bring increasing damages to the global fishing industries and trade. Warming ocean temperatures have led to the almost complete bleaching (and death) of the 2000 mile long Great Barrier Reef in Australia, wiping out a global treasure and major tourism draw for that nation.

We are also experiencing more severe heat waves, droughts, forest fires, crop failures and famines. The rise in temperature is causing a global increase in mosquito-borne diseases like Zika and malaria. We don’t have adequate vaccines for these diseases – particularly in the world’s poorest nations.

And we are paying a price for these and other climate catastrophes: In 2016 alone, we had $12 billion of climate-related disasters around the world.

2 degrees Celsius is the much talked about number in climate. Tell us what it means.

If global average temperature goes above 2 degrees, we’re getting into dangerous territory. It’s a threshold that we don’t want to cross over. And it has both political and scientific salience.

The science is simple. The atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gas emissions, which trap heat from the sun, is changing. For most of the past 10,000 years, the earth’s systems were in balance, fluctuating by only modest amounts – carbon dioxide and methane were being emitted at the same rate that they were being absorbed. But in the last 150 years, because of industrialization, changing energy demands and use of fossil fuel, these gases increased drastically. There is no uncertainty about the measurements.

The result has been that the Earth is getting hotter. Global average temperature has increased about 1 degree Celsius. This may sound minor but the damages we are already experiencing can be attributed to this minor change, and it is predicted to get worse as we approach or exceed 2 degrees.

The politics is also simple. Setting a global target enabled the world to coalesce around a concrete set of commitments to address climate change. And without such an agreement, we will not manage to solve the problem.

President Trump announced U.S. withdrawal from the Paris climate accord earlier this month. Why is this a big deal?

The United States was a leader in securing the Paris agreement, which has been hailed as one of the greatest achievements of global diplomacy in history. Virtually every nation in the world (and every developed nation), joined the pact in 2015.

Under the agreement, 195 countries with vastly different national interests, geopolitics and cultures agreed to reduce their climate pollution. Each country has enormous flexibility and control over how to protect its own populations from the costly and grave effects of climate change.

That the U.S. can walk away from something it was so instrumental in achieving is hugely damaging and an enormous setback. As the world reacts to this major about-face from the U.S. government, global leaders have stated that they will continue to move forward on the agreement. They realize this is an opportunity to boost their economies, add jobs, and usher in new markets and competition for their businesses and workers.

Is there any hope for the U.S. to keep up?

Across the U.S., 1,219 governors, mayors, businesses, investors and colleges and universities have declared their intent to support climate action and to ensure the U.S. meets its Paris commitments in the “We Are Still In” coalition.

States like Texas, Iowa, Oklahoma and Kansas are seizing the opportunity of climate solutions and leading the way in wind energy, creating jobs for their residents and propelling their local economies. North Carolina has emerged as a leader in solar power (third only after California and Arizona), putting its people to work in an industry that’s growing at record rates. Arkansas, Colorado, Michigan and Illinois are pursuing plans to increase renewable energy.

Clean energy jobs vastly outnumber fossil fuels jobs in the U.S., with the solar industry alone employing 30% more workers than the coal industry. This type of progress will continue, especially because American voters across party lines support climate action, clean energy policies, and limits on carbon pollution.

Furthermore, the nation’s largest and most profitable companies – including DuPont, General Mills, Apple, Google, Microsoft, PG&E, Walmart, and energy and oil companies like Exxon Mobil, BP and Shell — have acknowledged that climate change presents their businesses with both risks and opportunities and have plans to profit from clean, smart technology and energy efficiency.

However, it is unlikely that absent federal policy the U.S. will be able to maintain the significant trend in reductions required to contribute our share to the global solution. This will ultimately require Congress and the president to engage.

Can the U.S. still be a leader on climate?

Yes. Our innovation is second to none – and our states and companies can take advantage of that to excel. It would be much better if President Trump took advantage of this opportunity and encouraged investments in new, clean technologies. As prices continue to fall in clean energy, the federal government can be even more effective than individual states (which are already acting) in bringing markets to bear in solving climate change. The president should be increasing our clean energy export capacity and opening the door to commercial opportunities for American businesses and technologies, and for the things that American consumers want: clean air, clean and efficient cars, and affordable energy.

What is the process for U.S. withdrawal, and is it reversible?

Withdrawal from the Paris accord will take four years according to the process, and the president has said he will abide by the rules. Once a nation withdraws, it can decide to reenter the agreement at any point. Entering (or reentering) the agreement takes 30 days.

Is the Hewlett Foundation rethinking its environment grantmaking?

Periodically, we undertake a process to assess the effectiveness of our work to determine what changes, if any, are appropriate for our investments over the next several years. We’re doing that now with our climate and energy strategy.

We are receptive to creative ideas and connecting with leaders who will help us think creatively and realize new opportunities. We are focusing our efforts on achieving a long-term change, orienting our work around how to deeply reduce U.S. and global greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

While we are taking a long view, we are also taking up urgent matters. We have made some immediate changes to our grantmaking in response to the U.S. political landscape in order to preserve and defend as much of the gains of the past years as possible.

We believe in supporting as diverse an array of approaches, constituencies and voices – both out of a pragmatic belief that solutions can come from any angle, and out of an acknowledgement that solving climate change will require buy-in, commitment, and leadership from many different communities.

One area of grantmaking we’re developing is clean energy finance. The private sector’s leadership is essential to continue the momentum on climate mitigation, starting with companies and investors assessing and disclosing carbon risk information and then moving toward proactively investing in clean technologies to build infrastructure aligned with a low-carbon transition.

What’s needed in order for the world to achieve a two degree pathway is substantial: Tens of trillions of dollars – primarily private investments — must flow into low and zero-carbon infrastructure between now and 2030. Philanthropy should play a role in helping to mobilize private capital.

What can other foundations, donors, or investors do about climate change?

Less than 2% of all philanthropic dollars are going to solving climate change. We need foundations, donors and investors to step up now, especially as U.S. leadership has stepped down on this problem. We will do our part to encourage participation among our partners and colleagues. There is no better time than now for all of us to work together.