Q&A with Sarah Jones: How commissions shaped my career

From Mozart’s Don Giovanni to Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, commissions have long helped artists achieve their unique vision. And while today’s artists develop, fund and share their work in varied ways, commissions are still critical to fostering artistic expression. That’s why the Hewlett Foundation launched our Hewlett 50 Arts Commissions, which will support the creation of 50 exceptional works in the performing arts and their premiere in the San Francisco Bay Area.

From Mozart’s Don Giovanni to Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring, commissions have long helped artists achieve their unique vision. And while today’s artists develop, fund and share their work in varied ways, commissions are still critical to fostering artistic expression. That’s why the Hewlett Foundation launched our Hewlett 50 Arts Commissions, which will support the creation of 50 exceptional works in the performing arts and their premiere in the San Francisco Bay Area.

We spoke with Tony-award winning playwright and performer Sarah Jones about how commissions have influenced her own career, what they can do for other artists, and the piece the Hewlett Foundation commissioned from her last year to mark our 50th anniversary.

You’ve accepted commissions from organizations such as Equality Now and the National Immigration Forum, and your newest work — “Sell/Buy/Date” — was commissioned by the Novo Foundation. How have commissions affected your career?

These commissions have helped shape my entire career as an artist. Through each of them, I was afforded the opportunity to research and create performances on topics ranging from immigration to women’s empowerment. And each show featured perspectives and voices I seldom heard in the arts and entertainment marketplace. People often marvel at how I’ve been able to support myself as an artist and choose to work on topics I’m passionate about and perform for such a wide range of audiences — from people in prisons to mainstream theater audiences to heads of state around the world. The answer is the commissions I’ve received.

We recently launched the Hewlett 50 Arts Commissions to make grants to Bay Area nonprofits to commission new works from artists around the world. What do you think is the role of commissions in performing arts?

Commissions allow artists of every discipline to pursue their work in ways that would not be possible otherwise. In the current sociopolitical and economic climate especially, commissions enable artists to sustain themselves and maximize the attention they can give to work that matters most deeply to them.

As both an artist and a consumer of art, I find this freedom encourages artists to examine and spread ideas that prompt audiences to think more critically or feel more deeply about topics that they aren’t normally exposed to. Commissioned pieces help artists introduce audiences to ideas that can become part of the mainstream conversation, and this serves our culture more broadly.

How are artists funding new work?

Many artists rely on the commercial entertainment industry to sustain their careers, which has implications for how free they are to spread the ideas that inspire them, rather than just “what sells.” Many artists are also finding new ways to promote their work and reach audiences independently through online platforms that didn’t exist when I first began. This has helped some artists rise in visibility and influence in wonderful ways, without having to contend with “gatekeepers” who sometimes interfere with artistic creativity.

That said, with the rise of social-media driven, fame/celebrity-focused selfie culture, I have also remarked how artists, including myself, must adapt to maintain fidelity to their own creative visions while navigating the changing landscape. And I think this will all continue to evolve, shift and challenge artists in the years to come.

Do you think commissions can support artists starting out today?

In some ways, I think artists starting out today can avail themselves of even more opportunities for commissions than I had. Many philanthropic organizations and cultural institutions are now more committed than ever to commissioning work that might no longer be supported without a strong National Endowment for the Arts, for example, or might not be valued in an increasingly complicated marketplace, in spite of merit.

I recommend that artists scour the internet regularly for grants and commissions relevant to their discipline and area of focus, where they live, their ethnic and cultural background, gender, orientation, etc. And I’d encourage them to research the institutions that fund the kind of work they want to do, get to know who is responsible for commissioning work, and, if appropriate, reach out to people directly for suggestions and help. I also recommend artists approach this process with the help of a supportive community of peers and more experienced artists who can offer guidance. Even as a solo performer, it has taken a village of fellow artists and mentors to help me find my way.

What is it about the “one woman, many voices” style of much of your work that appeals to you as an artist?

For me, portraying people of many backgrounds, including those very different than my own, reminds me in a tangible way that we are far more connected than we are separate.

How did you develop the piece you created for the Hewlett Foundation?

The piece is an exploration of the views of various characters on the state of philanthropy in our country’s current sociopolitical and economic climate. As an artist, I have been a direct beneficiary of philanthropic giving throughout my career, and I drew from that experience as well as my understanding of the impact philanthropy has had on the lives of many millions of people in the U.S. over several generations. The Hewlett Foundation also facilitated interviews with key members of the philanthropic community, each of whom offered their own perspectives on the topic, and I added my own research on current questions and trends shaping the landscape to choose characters and create the premise of the piece.

Were there things about philanthropy that were revealed to you in writing the piece?

I discovered that as much as I thought I knew about the role of philanthropy in our culture, past and present, there was much I had never learned, such as how many of the institutions and programs I thought originated with our government — like the Head Start early education programs — were actually first conceived of, championed and funded by philanthropy.

You’ll perform the piece you created for the Hewlett Foundation’s 50th anniversary symposium again at the Center for Effective Philanthropy’s conference in April. Will it change in between the performances, and are your pieces ever really done?

Leonardo da Vinci is credited with saying: Art is never finished, only abandoned. In my work, I must try to strike a balance. For instance, at some point I had to lock my script for “Bridge & Tunnel” on Broadway. But since the pieces I create are often situated in naturalistic time and space and draw inspiration from the world around me, some are subject to change and evolution.

Changes may be as subtle as a date or the alteration of a character’s pop-cultural reference to aid the audience in understanding a concept, but I strive always for the core ideas and intention to remain consistent. In the case of the Hewlett piece, “The Foundation,” I don’t foresee many changes due to the particular unique realities of the unfolding events following the presidential election, which is when the piece is set.

Is there a commission from history that stands out for you?

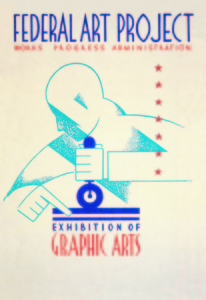

The most inspiring commission I know of was not given to one single artist, but to our entire country and ultimately the world. The WPA Federal Arts Project (ranging from visual art to theater to writing) gave artists the vital resources they needed to create some of the world’s enduring masterpieces.

These artists brought beauty and dignity into the lives of people who needed and deserved inspiration following the Great Depression. I hope we can take a page — or perhaps the entire book — out of that proud history.