Building wildfire resilience in the West

Historic and ongoing development patterns have placed many homes in high fire risk areas, with little to no consideration of that danger. This means a significant number of residents in the West live in homes that have not been built to accommodate fire on the landscape, putting communities at risk of losing lives and property, and requiring the deployment of significant and costly firefighting resources during wildfire events.

Finally, as clearly demonstrated through this year’s wildfire season, climate change has exacerbated the weather patterns and conditions that lead to conditions ripe for wildfire. Climate change leads to higher temperatures that dry out vegetation, prolonged drought, and more lightning strikes. A recent study found that climate change has already doubled the risk of extreme wildfire conditions in California. Much of the West was predicted to have higher than normal wildfire risk this year due to drought conditions.

Where will the Hewlett Foundation focus its efforts?

Many wildfire professionals have understood for decades that we need changes to the way wildfire management is approached in the Western United States. But a century of fire suppression and exclusion is ingrained in our culture and institutions. The Hewlett Foundation will focus on four major opportunities to further shift the West’s approach to wildfires to one that proactively works to create wildfire-resilient lands and communities. (Climate change is notably missing from this list of opportunities, reflecting our goal to coordinate with existing climate change mitigation efforts supported by the foundation.)

- Prescribed fire policy and management. Prescribed fire, also referred to as prescribed or controlled burning, involves intentionally lighting a fire in an area after careful planning and under controlled conditions to achieve specific natural resource management objectives, such as wildfire risk reduction, improved water quality, or improved wildlife habitat. Prescribed fire is currently underutilized as a management tool that can be safely used across private, state, and federal lands, including near developed areas, under the right conditions.

- Tribal leadership. Tribes throughout the United States have used fire as a resource and cultural management tool since time immemorial. After European settlement, Indigenous communities were largely prohibited from continuing their fire management practice, yet many remain uniquely positioned to provide leadership on wildfire policymaking and practice.

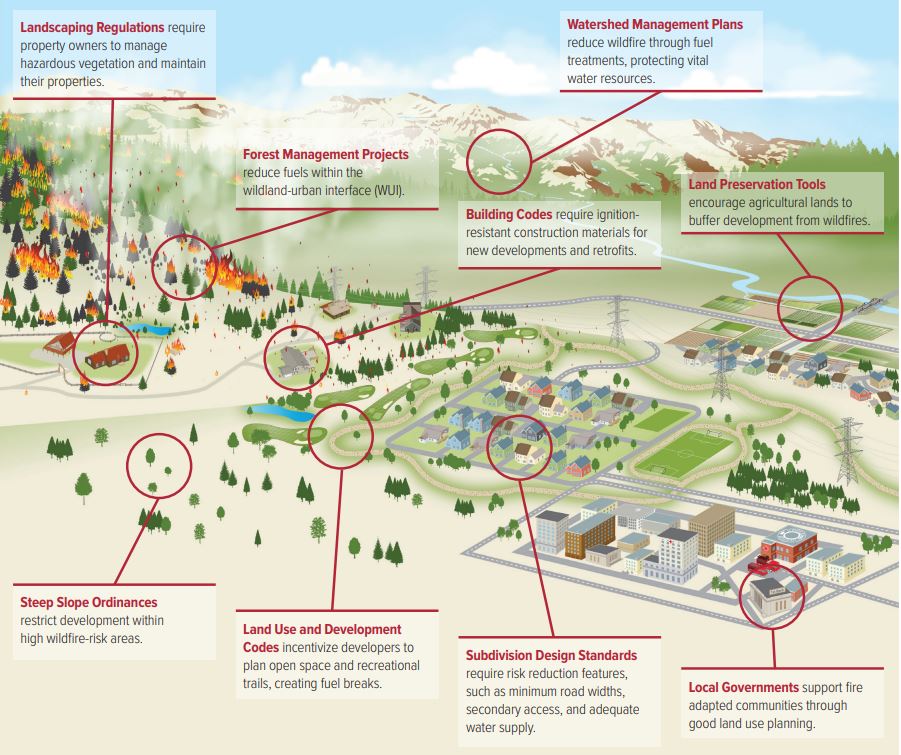

- Land use planning in the wildland-urban interface. Many communities in the Western United States were and continue to be developed with little to no regard for meaningfully reducing wildfire risk. Recognizing that fire is an inevitable and often necessary part of the landscape through the West, communities must become fire adapted. The alternative is continuing to lose life and property to extreme wildfire events. Land use planning includes a variety of tools local governments can use to better prepare its existing and future communities for wildfire risk.